Communication

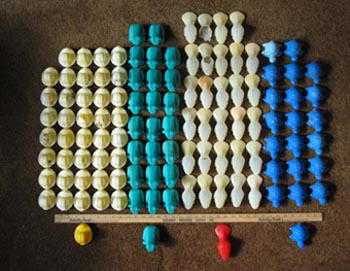

Moby-Duck

At the beginning of the war, two British chemists, V. E. Yarsley and E. G. Couzens, prophesied with surprising accuracy and quaintly utopian innocence what middle-class childhood in the 1970s would be like. “Let us try to imagine a dweller in the ‘Plastic Age,’†they wrote in the British magazine Science Digest.

This creature of our imagination, this ‘Plastic Man,’ will come into a world of colour and bright shining surfaces, where childish hands find nothing to break, no sharp edges or corners to cut or graze, no crevices to harbour dirt or germs, because, being a child his parents will see to it that he is surrounded on every side by this tough, safe, clean material which human thought has created. The walls of his nursery, all the articles of his bath and certain other necessities of his small life, all his toys, his cot, the moulded perambulator in which he takes the air, the teething ring he bites, the unbreakable bottle he feeds from . . . all will be plastic, brightly self-coloured and patterned with every design likely to please his childish mind.

Here, then, is one of the meanings of the duck. It represents this vision of childhood—the hygienic childhood, the safe childhood, the brightly colored childhood, in which everything, even bathtub articles, have been designed to please the childish mind, much as the golden fruit in that most famous origin myth of paradise “was pleasant to the eyes†of childish Eve. Yarsley and Couzens go on to imagine the rest of Plastic Man’s life, and it is remarkable how little his adulthood differs from his childhood. When he grows up, Plastic Man will live in a house furnished with “beautiful, transparent, glass-like materials in every imaginable form,†he will play with plastic toys (tennis rackets and fishing tackle), he will, “like a magician,†be able to make “what he wants.†And yet there is one imperfection, one run in this nylon dream. Plastic might make the pleasures of childhood last forever, but it could not make Plastic Man immortal. When he dies, he will sink “into his grave hygienically enclosed in a plastic coffin.†The image must have been unsettling, even in 1941; that hygienically enclosed death too reminiscent of the hygienically enclosed life that preceded it. To banish the image of that plastic coffin from their readers’ thoughts, the utopian chemists inject a little more technicolor resin

into their closing sentences. When “the dust and smoke†of war had cleared, plastic would deliver us “from moth and rust†into a world “full of colour . . . a new, brighter, cleaner, more beautiful world.â€

-- Donovan Hohn, "Moby-Duck, or, the Synthetic Wilderness of Childhood," Harper's Magazine, January 2007.

University of California, Davis

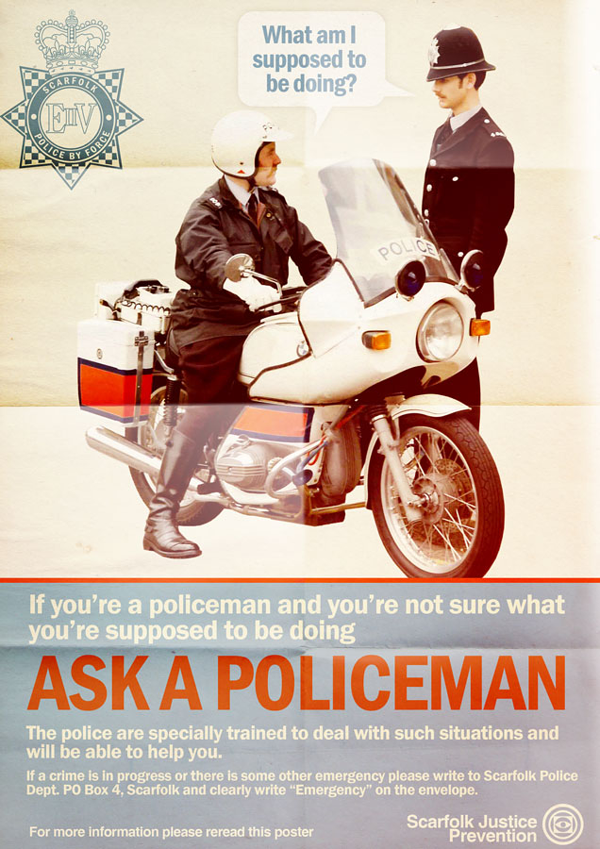

UC Davis pepper-spray incident

UC Davis spent thousands to scrub pepper-spray references from Internet

UC-Davis Paid $175,000 to Clean Up Its Image After Pepper-Spray Incident

UC Davis spends $175,000 to sanitize its online image after ugly pepper spray episode

UC Davis thought it could pay to erase a scandal from the Internet

Why UC Davis spent $175,000 to scrub references to pepper-spray incident

UC Davis got conned for $175K to erase pepper-spray incident from internet

The University of California paid $175K to scrub the internet of this picture

UC Davis paid at least $175,000 to improve online reputation after pepper-spraying students in 2011

UC Davis Tried Really, Really Hard to Erase That 2011 Pepper Spray Incident From the Internet

UC Davis spent $175,000 to bury search results after cops pepper-sprayed protestors

After “pepper spray incident,†UC Davis spent $175,000 to boost image online

UC Davis spent $175K to hide pepper spray cop on Google, says report

UC Davis Paid Consultants $175K to Remove Pepper Spray Images From Google

UC Davis Spent $175,000 to Eliminate Pepper Spray Cop From Its Google Search Results

UC Davis Spent $175K To Scrub Pepper Spray Cop From Google

UC–Davis Spent $175,000 Trying to Wipe the Internet of Its Pepper-Spraying Scandal

University of California, Davis Read More »

The Books-Internet

[T]he first visitors to the web spent their time online reading web magazines. Then came blogs, then Facebook, then Twitter. Now it’s Facebook videos and Instagram and SnapChat that most people spend their time on. There’s less and less text to read on social networks, and more and more video to watch, more and more images to look at. Are we witnessing a decline of reading on the web in favor of watching and listening?

Is this trend driven by people’s changing cultural habits, or is it that people are following the new laws of social networking? I don’t know — that’s for researchers to find out — but it feels like it’s reviving old cultural wars. After all, the web started out by imitating books and for many years, it was heavily dominated by text, by hypertext. Search engines put huge value on these things, and entire companies — entire monopolies — were built off the back of them. But as the number of image scanners and digital photos and video cameras grows exponentially, this seems to be changing. Search tools are starting to add advanced image recognition algorithms; advertising money is flowing there.

But the Stream, mobile applications, and moving images: They all show a departure from a books-internet toward a television-internet. We seem to have gone from a non-linear mode of communication — nodes and networks and links — toward a linear one, with centralization and hierarchies.

The web was not envisioned as a form of television when it was invented. But, like it or not, it is rapidly resembling TV: linear, passive, programmed and inward-looking.

The Books-Internet Read More »

Situational and Ambient Overload

Nicholas Carr, Roughtype:

One of the traps we fall into when we talk about information overload is that we’re usually talking about two very different things as if they were one thing. Information overload actually takes two forms, which I’ll call situational overload and ambient overload, and they need to be treated separately.

Situational overload is the needle-in-the-haystack problem: You need a particular piece of information – in order to answer a question of one sort or another – and that piece of information is buried in a bunch of other pieces of information. The challenge is to pinpoint the required information, to extract the needle from the haystack, and to do it as quickly as possible. Filters have always been pretty effective at solving the problem of situational overload. The introduction of indexes and concordances – made possible by the earlier invention of alphabetization – helped solve the problem with books. Card catalogues and the Dewey decimal system helped solve the problem with libraries. Train and boat schedules helped solve the problem with transport. The Reader’s Guide to Periodicals helped solve the problem with magazines. And search engines and other computerized navigational and organizational tools have helped solve the problem with online databases.

Whenever a new information medium comes along, we tend to quickly develop good filtering tools that enable us to sort and search the contents of the medium. That’s as true today as it’s ever been. In general, I think you could make a strong case that, even though the amount of information available to us has exploded in recent years, the problem of situational overload has continued to abate. Yes, there are still frustrating moments when our filters give us the hay instead of the needle, but for most questions most of the time, search engines and other digital filters, or software-based, human-powered filters like email or Twitter, are able to serve up good answers in an eyeblink or two.

Situational overload is not the problem. When we complain about information overload, what we’re usually complaining about is ambient overload. This is an altogether different beast. Ambient overload doesn’t involve needles in haystacks. It involves haystack-sized piles of needles. We experience ambient overload when we’re surrounded by so much information that is of immediate interest to us that we feel overwhelmed by the neverending pressure of trying to keep up with it all. We keep clicking links, keep hitting the refresh key, keep opening new tabs, keep checking email in-boxes and RSS feeds, keep scanning Amazon and Netflix recommendations – and yet the pile of interesting information never shrinks.

The cause of situational overload is too much noise. The cause of ambient overload is too much signal.

Situational and Ambient Overload Read More »