Environment

The Wilderness of Childhood

This is the kind of door-to-door, all-encompassing escort service that we adults have contrived to provide for our children. We schedule their encounters for them, driving them to and from one another's houses so they never get a chance to discover the unexplored lands between. If they are lucky, we send them out to play in the backyard, where they can be safely fenced in and even, in extreme cases, monitored with security cameras. When my family and I moved onto our street in Berkeley, the family next door included a nine-year-old girl; in the house two doors down the other way, there was a nine-year-old boy, her exact contemporary and, like her, a lifelong resident of the street. They had never met.

The sandlots and creek beds, the alleys and woodlands have been abandoned in favor of a system of reservations -- Chuck E. Cheese, the Jungle, the Discovery Zone: jolly internment centers mapped and planned by adults with no blank spots aside from doors marked staff only. When children roller-skate or ride their bikes, they go forth armored as for battle, and their parents typically stand nearby. . . .

The endangerment of children -- that persistent theme of our lives, arts, and literature over the past twenty years -- resonates so strongly because, as parents, as members of preceding generations, we look at the poisoned legacy of modern industrial society and its ills, at the world of strife and radioactivity, climatological disaster, overpopulation, and commodification, and feel guilty. As the national feeling of guilt over the extermination of the Indians led to the creation of a kind of cult of the Indian, so our children have become cult objects to us, too precious to be risked. At the same time they have become fetishes, the objects of an unhealthy and diseased fixation. And once something is fetishized, capitalism steps in and finds a way to sell it.

What is the impact of the closing down of the Wilderness on the development of children's imaginations? This is what I worry about the most. I grew up with a freedom, a liberty that now seems breathtaking and almost impossible. Recently, my younger daughter, after the usual struggle and exhilaration, learned to ride her bicycle. Her joy at her achievement was rapidly followed by a creeping sense of puzzlement and disappointment as it became clear to both of us that there was nowhere for her to ride it -- nowhere that I was willing to let her go.

-- Michael Chabon, "Manhood for Amateurs: The Wilderness of Childhood," New York Review of Books, July 16, 2009.

The Environmental Movement Isn’t Big Enough

As politics gets slower, global warming speeds up. The problem isn't feckless officials. Obama has a dream team of climate specialists: Clinton administration EPA veteran Carol Browner as energy czar, Harvard physicist John Holdren as top science advisor, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Steven Chu as Energy secretary and Oakland activist Van Jones as White House green jobs coordinator.

And the problem isn't that environmental groups aren't working hard enough. I've never seen them work more tirelessly, with lobbying efforts in capitals around the world.

In fact, the problem is pretty simple: The environmental movement isn't big enough. It's one of the most selfless of advocacy efforts. But the movement has been sized to save whales and build national parks and force carmakers to stick catalytic converters on exhaust systems. It's nowhere near big enough to take on the fossil fuel industry, the biggest player in our global economy. It's like sending the Food and Drug Administration to fight the war in Afghanistan.

Exxon Mobil Corp. made more money last year than any U.S. company in the history of money. . . .

The news coming out of world capitals makes it clear that we need more than lobbying by environmentalists to get the changes the science demands. We need a movement, a groundswell, to give those lobbyists the clout they need. But we can make it happen only if we join together fast.

-- Bill McKibben, "Can 350.org Save the World?," Los Angeles Times, May 15, 2009.

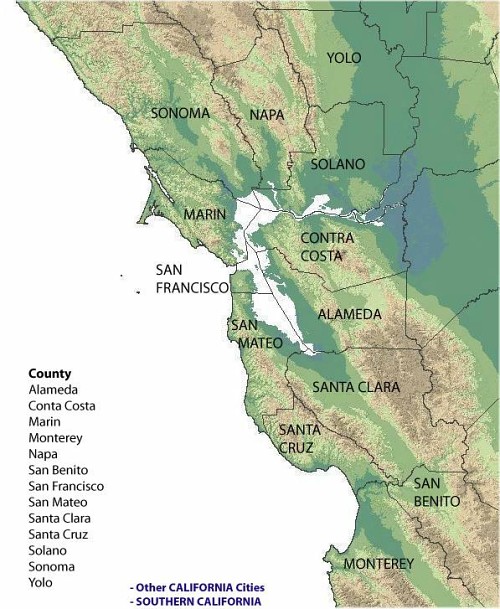

Some SF Bay Area Environmental Event Calendars

Own Events and Others' Events

Acterra EcoCalendar

Bay Nature Events Calendar

Ecology Center EcoCalendar

Global Exchange Bay Area Events

Indy Bay Event Calendar

San Francisco Bay Area Progressive Calendar

Own Events Only

Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy Events Calendar

Save the Bay Events

UC-Berkeley College of Environmental Design Events

The Nature Conservancy

I had been much impressed with the Conservancy's way of doing business. Unlike most environmental organizations, which rely on political lobbying and legal action to get results, the Conservancy was into land brokering. While its cadre of scientists compiled a vast data bank on endangered flora and fauna, its field staff concentrated on "doing deals" with individual and corporate landowners, working out tax breaks and other incentives as a way of acquiring threatened ecosystems and essential habitat for endangered species. What I had particularly liked about the organization was its pragmatic attitude: These were people who could have been very successful developers and real estate brokers, yet in contrast to that unlovely tribe, they were using their wheeler-dealer skills to save, rather than destroy, the natural world.

-- Don Schueler, A Handmade Wilderness (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996), 274.